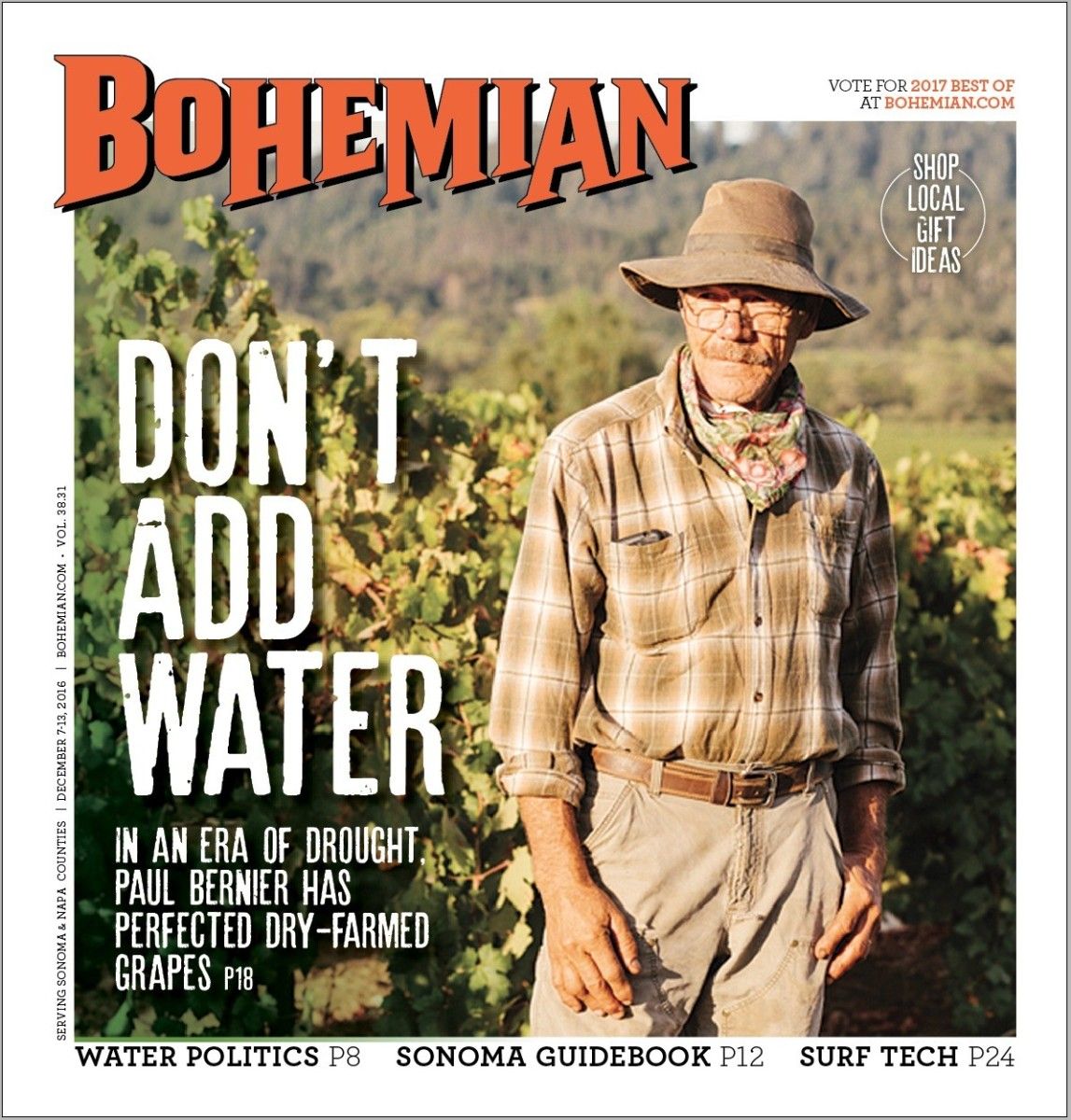

Dirt Farmer

Paul Bernier’s vines are celebrated for what they lack: water

Early one morning in September, Paul Bernier prepares for a day of work in Healdsburg’s Dry Creek Valley. He grabs a mortar and pestle, a sugar meter, a sack of home-dried pears and a three-foot-long temperature probe. We pile into the cab of his scruffy pickup, dogs in back, and bounce down the road. We’re going to spend the day working the dry-farmed Zinfandel vineyards he manages. But this time of year he doesn’t call it work; he calls it “goofing off.”

Bernier, 65, is lanky, with a head of darkish, curly steel wool and an impish grin. A farmer at heart, he settled on grapes by way of attrition. Grapes were the one crop he didn’t kill.

“I’m not too sensitive around plants,” he says. “But grapes can stand me.”

Bernier’s methods do at times appear to push the boundaries of tough love and benign neglect. But for all of his professed horticultural limitations, his services are in high demand. And he only takes on the hardest cases.

“Most of my grapes are on marginal land,” Bernier says. Which is to say, old vines, usually hearty Zinfandel grapes, clinging to thin-soiled hillsides, planted by stubborn Italian immigrants.

These “old Italian guys,” as he calls them, began hiring Bernier to implement their methods when they became too old to do it themselves. By way of micromanaging him, these growers initiated Bernier into an agriculture practice that is still very much alive in the Mediterranean basin (which includes parts of Europe, Asia and North Africa) and is catching on in California. That an insensitive plant person like Bernier, who grows grapes on the steepest, boniest hillsides he can find, can produce such impressive yields is a testament to the power of these methods. They boil down to one simple, if counterintuitive, practice: don’t water the grapes.

Dry farming came over from the Mediterranean with Bernier’s mentors. It depends on wet winters and dry summers, also known as the Mediterranean climate, which California famously has. There are dry-farming methods used in the East Coast and Midwest that depend on summer rains, but the aim of Mediterranean-style dry farming is to store as much of the winter rains in the earth as possible. The following summer, when it hasn’t rained for months, dry farmers like Bernier won’t give their crops a drop, because they don’t need it. In fact, surface irrigation would only water the weeds. Vines that have been weaned from irrigation, on the other hand, grow deep roots with which to tap those stored winter rains.

As Bernier learned and refined the techniques passed on to him by the old Italian guys, he built a reputation as a rescuer of vineyards on the edge of failing, regularly coaxing three to four tons’ worth of grapes from an acre of dry hillside. If he were growing on prime, valley bottomland, and irrigating his grapes, he says he’d get closer to six. But then his grapes wouldn’t be in such high demand.

Bernier calls himself a sharecropper. It’s a humble word in California’s high-brow wine community, but entirely accurate. He cultivates vineyards on other peoples’ land, in exchange for 65–85 percent of the harvest. Many of his clients come to him because they’ve heard he can rescue the dying vineyards that experts have told them should be torn up. And winemakers seek out his harvests, because it turns out that grapes grown on marginal land, without irrigation, produce some great wine.

Our day includes a stop at Dry Creek’s Nalle Winery, for a quick tour and a sip of wine. Andrew Nalle, the manager and owner, uses Bernier’s grapes in his Bernier-Sibary Zinfandel, Nalle’s top-selling label, and his Dry Creek Zin blend. All three of Nalle’s top-selling wines are from dry-farmed grapes. The wines are remarkably dry and smooth for Zinfandels, with all of the dark complex mystery that Zins often miss because of the higher alcohol, fruit laden–style produced by irrigated vines.

The flavors imparted by dry-farmed grapes “are more vibrant, and linger longer,” Nalle says. “The sugars are more in line with the ripeness of the fruit. The sweetness matches the flavor.”

Later in the day we do a similar drill at Peterson Winery, also in Dry Creek, where Tom Peterson explains how it is that dry-farmed vines produce superior grapes.

“The plants aren’t there to make you wine,” Peterson says. “The fruit exists to disperse the seeds. So the seeds need to ripen at the same time that the fruit ripens. In the vinifera [grape] family, the vine wants to grow like hell, above the other plants. When you irrigate the vines, it tricks them into thinking they should keep growing.”

When the sugars are where you want them for winemaking, the fruit doesn’t have any flavor and the seeds aren’t ripe, he says. The fruit isn’t physiologically mature. “The nuances that make great wine happen in the last few weeks of the grape’s maturation. If they ripen too quickly, they don’t develop the esters and aromatics that attract creatures.”

Also, Peterson notes, the deeper roots tap into mineral flavors from down below, adding to coveted claims of terroir.

When one considers the water savings associated with dry farming, plus the higher quality of produce and higher price it fetches, it should all amount to more than enough incentive for a farmer to give it a shot. But the advantages don’t end there.

“I dry-farm because I’m lazy,” Bernier says, with a coyote’s glint in his eye.

He’s kidding, of course. Sort of. Bernier keeps a ferocious pace through the day. But there is an undeniable time-savings enjoyed by dry farmers that can’t be ignored. They don’t need to bother setting up, operating and repairing irrigation equipment, much less paying the associated costs. Bernier says he can manage an acre of wine grapes for only about $1,800 a season, compared to the $5,000 per acre charged by the average irrigated vineyard manager.

That cost savings, combined with the premium Bernier can charge for his grapes, more than makes up for the slightly reduced yield a dry farmer can expect. In late summer, when I visited, there isn’t much for Bernier to do but monitor the sugar content of his grapes and taking his compost pile’s temperature.

The old timers, Bernier explains, have so little to do this time of year, they would “hit them with sulphur, pack up their wagons and go fishing for rock fish and abalone at the coast.” They wouldn’t come home until it was almost time to harvest the grapes. Bernier keeps this tradition alive in his own way. Walking through downtown Healdsburg one day, he pulls out his camera and shows me a selfie he took 300 feet up a redwood tree, a half-day climb. He also does a lot of sailing with his grandkids on Lake Sonoma above Dry Creek Valley—a reservoir that, ironically, was created in part to capture water with which to irrigate grapes.

Grapes aren’t the only crop that can be dry-farmed in California. Early Girl tomatoes from Monterey Bay are legendary for their rich flavor and surprising juiciness. There are dry-farmed potatoes, squash, quinoa, apples and nuts, as well as the juiciest melon you will ever try—the Crane melon from New Family Farm in Sebastopol. Even almonds, perhaps the most notorious of California’s water-wasting crops, can be dry-farmed. Indeed, almonds once thrived, water-free, in San Obispo, southern Monterey County and in the Sierra Foothills.

While there is a lot of pre-harvest goofing off to do later in the year, a dry farmer has to pay his dues in spring. When the rain stops and the soil dries, a dry farmer gets cultivating. This means working to break up the soil, uprooting the weeds and generally disrupting the ground’s structure, especially the soil capillaries formed by escaping water that become conduits for more water to follow.

Bernier only works with “head-trained” vines, which are free-standing little trees, rather than viney plants that hang on trellises. He uses a small, crawling tractor to cross-cultivate his grapes on two axes, something you can’t do with trellised vines. The work, he admits, “can be a bit diesel-intensive.”

After cultivating, the broken earth is left to dry into dust as the summer wears on. With no irrigation happening, weeds don’t have a chance to get started. And without any capillary structure to the soil, the dry earth acts like a seal, keeping the moisture in. In the heat of summer, the water “wants” to get out of the ground and into the dry air. The dry farmer gives the water no avenue of escape but through the plant.

In between visits to local wineries, we make the rounds of the “ranches,” as he calls them, that Bernier manages. (He also has a few acres planted at home, which he calls Paul Bernier Zinyards.) At each stop, his dogs, Finn and Wasabi, scamper about, sniffing at the bases of the vines, chasing mice and nibbling the occasional fruit, as does Bernier.

As he cruises his ranches, Bernier effuses old-Italian-guy wisdom. He points out the various grape varieties, which he can distinguish according to the differing hues of green in their leaves. While all of his ranches grow primarily Zinfandel, they contain other varieties, such as Carignane, a classic blending grape.

“Back in the day,” says Bernier, “they would hide Carignane underneath the Zinfandel vines, because they bear more and are worth less.”

The ranches also grow the occasional Petit Syrah, Cabernet Sauvignon and other varieties. Those are fine, Bernier says, but he avoids white wine grapes. “They’re too fussy.”

Sensitive, that is.

At each stop, Bernier grabs grapes from a scattering of vines. Back at the truck, he mashes them together with a mortar and pestle, and pours the pulp into the brix meter. After registering the sugar content of the vines at each ranch, Bernier tips back the leftover grape juice.

The first grapes in California were dry-farmed. The practice was still commonplace, but on the decline, in 1976. That year, dry-farmed Napa Valley wines swept the prestigious Paris Tasting Competition, which was expected to be won by French wines. It was a watershed moment for California wine, and put the Napa region on the map as a wine heavyweight.

Irrigation was first brought to California’s wine country in the form of overhead sprinklers that were initially used to thwart frost in spring. In freezing temperatures, a coating of water will shield the emergent buds, buying a few precious degrees of wiggle room.

Growers quickly realized that irrigating throughout the growing season would produce larger yields, and the practice became widespread. In 1971, drip irrigation arrived in Napa, and was hailed as water-saving technology at the time.

Thus, as dry-farmed California wines stole the 1976 show in Paris, drip irrigation was steadily advancing into wine country. As it did, yields and acreage began to grow, many say wine quality began to suffer and the water table began to drop in some areas. Though California’s surface water has been carefully regulated for more than a century, its subsurface water has not. “Whoever has the deepest straw gets the water,” Bernier laments. (But that’s about to change. See News, p8.)

Those deep straws have replaced the deep roots that grape vines would normally grow. Instead, thanks to drip irrigation, grape roots congregate near the drip nozzles at the surface, rather than going to the trouble of plunging deep into the terroir-rich earth in search of moisture. The shallow roots, as well as other softening effects of too much water—mold, for example—are a big reason why it’s common for vineyards to be torn up and replaced every 20 years.

Dry-farmed vineyards, by contrast, can produce for centuries. There are still a handful of vineyards in Sonoma, Napa and San Joaquin counties that haven’t been watered since the 1800s, if ever. Today, wine grapes are dry-farmed as far south as Paso Robles.

Dry Creek, and the Russian River it feeds, are salmon and steelhead streams. But in 2001, only 10 coho salmon returned to the river. Since then, over

$10 million has poured into restoring salmonid habitat, resulting in only marginal improvements that have been severely hampered during the drought. The National Marine Fisheries Service lists agriculture as the number one threat to the Russian River coho. And by “agriculture” they mean vineyards.

Between 1997 and 2013, Sonoma County vineyard acreage grew from 40,001 to 64,073 acres, according to the Sonoma County Agriculture Department, with most of that expansion occurring in the Russian River watershed.

Sonoma County, like many parts of California, is currently home to a heated battle over water. Residential landowners are being told they can’t sprinkle their lawns, while grape growers are left to self-police their own water use, unmetered. Vineyard wells put tremendous pressure on the aquifers, while many pump water directly from creeks and the river, with intake pipes as wide as 24-inches across. The vineyards pump not only for irrigation, but for frost protection as well—the timing of which puts immense pressure on the waterways, and the fish that live there.

While dry farming has become a buzzword of late, it’s what Bernier does with his compost that has allowed him to excel. The old Italian guys taught him to pile pumice—the remains after pressing—around the base of the vines. Eventually, Bernier began composting his pumice, and bringing it to his vines by the wheelbarrow load. One fall, he ended up making a bigger pile of compost at the base of a particular vine, such that it piled around the vine’s trunk. The following spring, he noticed the excess compost, and pulled it off the vine.

There were grape roots crisscrossing the compost. The plant had sent roots through its own bark, straight out of the trunk and into the compost.

“The plant sensed the nutrients and wanted it,” Bernier says. He’s been laying it on thick ever since. Today, he puts 30 tons of pumice compost on each acre of grapes. Compost is the only thing Bernier irrigates.

The piles live on rented land, and Bernier pays rent by assessing a fee to wineries in exchange for permission to dump their waste from pressing. They pay him, in other words, to deliver the raw materials for the compost in which his success is rooted.

When we arrive, the 100-yard piles are steaming. As his dogs frolic about and munch the gorgeous, multicolored pumice, Bernier sticks his thermometer into the center of the pile and takes its temperature. Then he shows me the compost turner that he designed and built, fashioned from old truck parts. Bernier is, at heart, an engineer and tinkerer. The design of his compost turner has been widely copied by farmers from as far away as India.

As we stand among his piles, Bernier points to some grapes on a neighboring property. Irrigation pipe weaves through the trellised plants. The same nozzles used to deliver water, he says, often pump fertilizer to the plants as well, in a process dubbed “fertigation.”

Vines become addicted to fertigation, Bernier says, “like the alcoholic who shows up at the bar at 6am waiting for it to open.”

Bernier compares these vines—addicted, helpless and disoriented—to dry-farmed vines. “When you add water in summer, it sends the plant mixed messages. They don’t know if it’s May or July or whatever.”

With a mix of pity and bemusement, he waves at the fertigated grapes next door, in front of a large house with a manicured green lawn.

“They don’t know if they’re coming or going,” he says.

And then we go back to goofing off.